All this month I am writing about the marvellous Indian handlooms, a quick but captivating dive into the saree specifically, a garment worn by Indians for five millennia. Come with me into the magnificent, complex and utterly fascinating world of fibre and yarn, of skills and techniques of dyeing and printing and embroidery, traditions unchanged for centuries. Of sumptuous finished fabrics that not only make a fashion statement, but also constitute our cultural heritage and political identity.

M is for Myriad Motifs

We could talk about many sarees here - the Maheshwari, Mangalgiri, Moirang Phee, or materials like Matka and Muga silk, or Mashru - the list is endless. Couldn't make up my mind! So I'm going to talk about the motifs in Indian sarees instead. They too number a million, so this is by no means exhaustive.

Bear in mind that India is a diverse nation - 22 officially recognised language groups spread over 28 states and 8 union territories, each with their own micro-environments. A dozen or so faiths/systems of spiritual beliefs, landscapes ranging from tranquil, flat coastal to deep tropical forests to snowy Himalayan to arid desert and everything in between. Now add to that a layered history of migration, trade and cultural exchange through five millennia and you get a melting pot influencing the design vocabulary of the saree. We have already seen in an earlier post how the Ganga-Jamuna border design element has diffused into regions where neither of the two rivers are present.

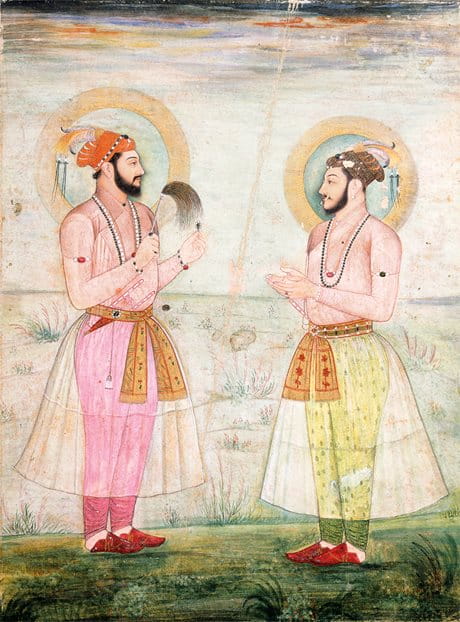

Many of the motifs draw inspiration from Indian mythology, local temple architecture, flora and fauna and natural elements. As mentioned before, the Mughals meshed design concepts from their original Persian motherland with Indian traditions, Mughal and Islamic aesthetics have moulded the textile industry in a major way. Indian handlooms have a wide range of motifs combining the most ancient with these medieval influences. Of course, design is not static, the current generations of textile designers draw upon the traditional to devise modern ones, so that the design pool is always evolving and expanding.

Here are some major design motifs used in sarees. I'm using English as the names of the motifs vary across India among different language groups. Mayur in Bengali becomes Mor in Hindi and Mayil in Tamil, they all mean the same thing.

Animal motifs - Lion, Tiger, Deer, Cow, Elephant etc. Each one symbolises a unique quality and significance. The deer for example embodies grace and gentleness. Includes mythical animals like the Winged Horse.

Birds - Traditional ones are the Peacock, Peacock 'eye,' Swan (Hamsa/Hans), Parrot, Cuckoo 'eye', Cranes. Also include mythical ones like the two headed Eagle. Modern motifs like the Flamingo are seen in Batik sarees.

Chariot - a wooden vehicle on which deities are placed are drawn, of special significance in Hindusim. Lord Krishna was the charioteer of Arjun in Mahabharat, an important epic.

Conch - connected to Hindu mythology and blown at religious rituals. A signifier of auspiciousness.

Coconut - often on a pot called the Kalash or Kumbha. Another item used in prayer/rituals and considered auspicious.

Fish - motif popular in the East. Fish is considered auspicious as in Indian mythology, Vishnu came to the Earth as a giant fish to save Manu (the first man) and the Vedas from a great deluge.

Flowers - can be individual or clusters. Called the 'buti' if small and 'buta' if large. Many are depicted, of special importance are the jasmine, rose, marigold, tulip, crocus, iris, narcissus, and the champaka. Flowers are offered to deities in temples and private shrines, they are symbols of beauty and grace. Several were introduced from foreign lands and included in the Indian repertoire. Floral motifs were expanded under the Mughal rulers as Islam frowns upon the depiction of figures. They are used extensively in Benarasi sarees. Read more about flower motifs here.

Geometric - various types of geometric motifs, stripes, checks and pattern repeats may be used, especially in the aanchal and borders.

|

| A combination of floral and geometric motifs in this cotton handloom from Bengal. Note the small flower/ leaf 'buti' in the body of the saree. |

Lotus - this flower deserves a separate discussion. The lotus is a recurrent motif across India because it has a special significance in Hinduism. It grows in mud but is untouched by it, symbolising purity, creation and detachment from the material world. Deities are often depicted seated on the lotus or carrying one. The lotus motif in sarees can be an 8 petalled or a 100 petalled one. Viewed from above or in profile. Read more about the Lotus in textiles here.

|

| Image source Lotus motif in ikat |

Hunting scene or Shikargah - the hunter, elephant, deer, lion/tiger depicted among trees/forest without any actual violence taking place. A tranquil celebration of animals and humans. Read more about the motif here.

Leaf - The heart shaped leaf Sacred Fig (Peepul/Ashwatha) tree is revered as Buddha attained enlightenment under one and is represented on sarees and other textiles. The Tamarind leaf is also a motif used in sarees.

Mango - a greatly popular motif across India - the mango is symbolic of fertility and auspiciousness. The fruit is depicted on all kinds of textiles, shaped similar to the next one.

Paisley - a more elaborate flower or flowering vine in a teardrop shape, the tip of the drop drooping slightly. Or a vase with a bouquet of flowers. The paisley started off in India in Kashmiri weaving and embroidery, especially in their luxurious pashmina shawls. Originating in Persia, it was called boteh or buta here. These shawls carrying the characteristic motifs became extremely popular in the West. With the invention of the Jacquard looms in the 19th century, cheaper imitations of the Kashmiri patterns were woven in Paisley in Scotland, and so the motif came to take on the name of the town.

Rudraksha - the dried fruit of the Rudraksha tree, held to auspicious. 'Rudraksha' is believed to have originated from Lord Shiva's tears. Rudra is a name for Shiva, aksha means eye. Often used as a talisman.

|

| Rudraksha motifs on a Kanchipuram silk. |

|

| Rudraksha motifs on a Sambalpuri silk from Odisha. |

Read more about sarees motifs here, here and here.

~~~

Did you know that mirror work, sewing in small pieces of mirror, into a fabric, originated in Persia and was brought to India in Mughal times? It was adapted into the local repertoire particularly in the Western Indian states of Rajasthan and Gujarat where it became a characteristic style.

Thank you for reading. And happy A-Zing to you if you are participating in the challenge.